Costume Design of Don’t Stop the Carnival!

A Historical Investigation, Playscript Analysis & Visual Rendering

Annotated Website

by Kaedra Lynn Herink

School of Dance, Theatre & Arts Administration

Submitted to The Honors College at The University of Akron

Honors Faculty Advisor: Adel Migid

Readers: Irene Mack-Shafer & Aubrey Caldwell

Inception: September 2013 – Completion: April 2014

Introduction to Don’t Stop the Carnival

The Novel

Don’t Stop the Carnival is a fast-paced, comedic, and adventurous novel written by Herman Wouk in 1965. This 1950’s-era story follows Norman Paperman, a middle-aged Broadway public relations agent eager to escape his current life and career. After a heart attack caused by a rapid and high-stress environment, he decides to fly to the fictional island of Kinja to scope out a new business venture. He falls in love with the Caribbean, and makes the decision with his wife Henny to purchase the Gull Reef Club. But the façade of an island paradise crumbles quickly, as one gigantic problem after another occurs at Norman’s establishment. Falling in love with a faded movie star named Iris, battling the machete-bearing brute Hippolyte, facing countless water shortages, and making the passage from tourist to local are just some of the events Norman encounters. After it all becomes too much for Norman, he and Henny decide to return to their life in New York City and sell the Gull Reef Club to another owner.

First edition cover art.

The novel is written in the 3rd person omniscient narrator form. Yet Norman is in almost every scene and chapter – giving the reader the feeling of misunderstanding and being an outsider. The reader, like Norman, views the Caribbean through the eyes of an American. Events unfold as they are happening in the story; there are no flashbacks or flash-forwards.

A few major themes are present in Don’t Stop the Carnival. These include fantasy vs. reality, outsiders vs. insiders, morality vs. immorality, and sanity vs. insanity. Tourists often see the Caribbean as a tropical paradise or fantasy, but Norman learns through experience that reality is much different. Culture and morals on the island differ greatly from what Norman is used to. Through a rollercoaster ride of sanity and insanity, he makes the transition from outsider to insider by the end of the novel.

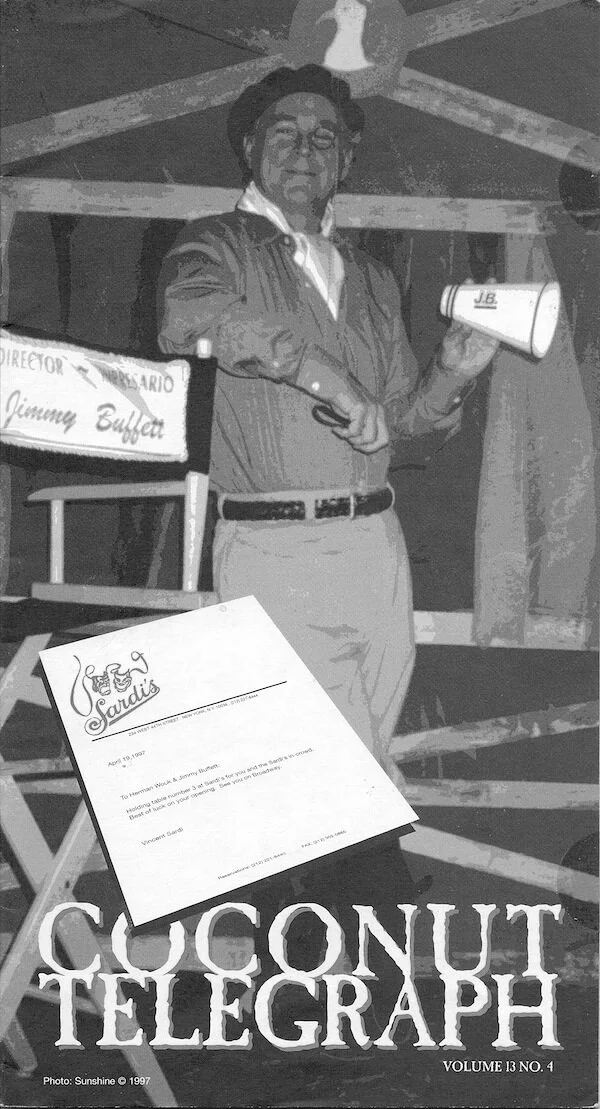

While the novel is lesser-known in America, it has made its impact in the Caribbean. “Every sailor, hotelier and bartender seemed to have a copy of Herman Wouk’s novel sitting around. The moment [Buffett] read it, he understood why Don’t Stop the Carnival was, and still is, the sailors’ bible to understanding life in the islands.” (Coconut Telegraph, 1997). Buffett explains, “Herman went away and didn’t realize the impact he’d left on the Caribbean culture. Hotel owners that I run into, anybody that lives and exists in the Caribbean knows Don’t Stop the Carnival. It’s like a bible. But he had no idea this was going on.” (Buffett, Coconut Telegraph, 1997). The book inspired Buffett to contact Herman Wouk with his ideas to turn the tale into a musical. And he alone succeeded in overcoming Wouk’s “steadfast resistance of nearly thirty years to proposed Broadway, film, and television adaptations of Don’t Stop the Carnival.” (Humphrey & Lewine, 1996).

Development of Novel into Musical

After much collaboration, rehearsals began for Don’t Stop the Carnival! at the Coconut Grove Playhouse in Miami, FL (Humphrey & Lewine, 1996). While Wouk outlined the libretto, Buffett wrote the lyrics and music, drawing on his skills of storytelling and melody (Buffett, Coconut Telegraph, 1998). When asked about his process, Buffett said:

I approached it as a show. I love Calypso – I can listen to a great Calypso band, I can have two or three glasses of wine, and I can dance the merengue all night, but that’s me. You have to disassociate your own personal thoughts about things because you’ve got paying customers out there. Again it comes back to my close personal attachment to the audience. Who’s the audience going to be for this? How much of this can they take? Calypso music, yeah, I can listen to it all night, but I know an audience can’t. …. You’ve got to know what you’re doing. So Calypso is going to be the backbone of the music, but I wanted to go off in tangents. I wanted to go to reggae, I wanted to go to soca, to zouk, and a little bit of merengue, so you could break up the pace. I’m not a great singer, I’m certainly not a good musician – I’m passable. I’m a fair writer, but my strongest suit is I can read an audience and pace a show. I’ve been doing theatrical things in my show for the past five years. (Buffett, Coconut Telegraph, 1997)

Carnival! opened on April 19, 1997 with mixed reviews. Most of the reviews wrote positively about the musical, but many agreed that it needed more work to be a true hit. The music, lyrics, cast, band, and visual elements were praised; the editing and directing were most heavily criticized (Dolen, 1997). The show closed on May 18th, 1997 and received a total of 14 Carbonell award nominations in the 1996-1997 regional theatre season (Sommers, 1997).

Lack of Archival Material

Due to the short life of the musical and copyright restrictions, there are no public copies of the libretto to view or purchase. Jimmy Buffett purchased the rights to Wouk’s novel (Beckwith, 2009) and the libretto has not been released in any format. Short commentary by Wouk and a book of song lyrics accompany the CD (Buffett, Don’t Stop the Carnival!, 1998). An adapted libretto was formed for this project through the lyrics, the music, the original source material of the novel, and extensive research of theatrical reviews and commentary.

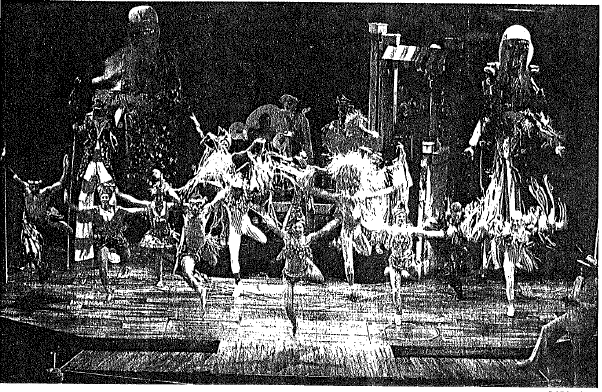

Only a few black and white photographs of the production are known to exist; four of which are published in the Coconut Telegraph periodical. A few additional photos were found in various Florida newspapers. Only one photo was found online, which was scanned in from a a newspaper. While this makes analyzing the original production very difficult, it provides an opportunity for a fresh design not influenced by the original team of designers. This project focuses on new costume designs for the musical.

Gallery of photos retrieved while doing extensive research. Credits to publicity photographers and artists at The Floridian, The Miami Herald, The Sun-Sentinel, The Palm Beach Post, & The Coconut Telegraph.

Author’s Note

I owe a great deal of thanks to my father, John Herink; as well as Steve Hersh at the University of Miami Libraries (Special Collections). Without the help of these two, I wouldn’t have any access to rare archival material.

The only way I was able to retrieve any of the black and white photos shown in the gallery above (except for one!) is from their help.

Mr. Hersh scanned countless numbers of articles and archival data from the Coconut Grove archive. The Coconut Grove theatre does not exist any more; so I was unable to contact them directly. A number of the newspaper records had photos and other promotional information. I also received a detailed list of everyone who was involved in the production.

My father John surprised me in January (2014) when he said he might have an article or two – maybe a coconut telegraph that might mention Carnival! – and returned with a stack of Coconut Telegraphs dating back to the 1980’s! I had a whole archive of information in my basement and I didn’t even know it. There is a lot of information in this project that references these Coconut Telegraphs.

This is all very exciting to a researcher when there is minimal information about a topic – and nearly nothing useful on the Internet! I learned a lot about digging for research without using the great resource of the WWW that I was accustomed to.

Historical Research

Time Period

The time period of the novel is set in the late 1950’s. World War II was just over a decade in the past. While more women joined the work force in America, progress was much slower in the Caribbean (Gilmore, 2000, p.155). Female teachers were required to resign upon getting married until the 1960’s (Gilmore, 2000, pp.146-147). “The assumption that married women had no place in the world of employment because they would be provided for by their husbands was widespread and continued to receive official sanction in parts of the Caribbean until very recently,” (Gilmore, 2000, pp. 146-147).

Tourism to the Caribbean began to boom in the 1950’s, a few years before the setting of Don’t Stop the Carnival (Padilla, 2003). The characters in the novel are immersed in the height of the tourist boom (Wouk, 1965). Gilmore (2000) explains that this was due to cheap and reliable air transport that came about in this decade (p.42). Still, this travel was a luxury for the middle to upper class.

The environmental and social issues that Norman Paperman has to deal with in the novel are a very accurate representation of what life was like at this time. Tourism in the Caribbean put stress on already problematic water resources and waste disposal (Gilmore, 2000, p.79). This tourist boom created many hotels and jobs, but growth was so rapid that there was little planning in terms of the environment and the culture clash (Gilmore, 2000, p.12).

This mix of cultures had a direct impact on fashion: “The growth of the tourist industry throughout the Caribbean region has attracted many visitors to the island nations. This has led to further commingling of various dress customs, creating more diversity in fashions and the emergence of a vibrant local clothing business for the tourist market,” writes Buckridge (Overview of the Caribbean, 2010).

Locales

The two location settings for Don’t Stop the Carnival are New York City and the fictional Caribbean island of Amerigo, or “Kinja”. These physical environments are direct opposites at certain times of the year, and fashion varies immensely.

In New York, a wide range of clothing is needed due to temperature extremes. Average temperatures range from 23°F to 83°F; record temperatures range from -4°F to 102°F (Cornell University). There is consistent rain year-round, and winds bring cold, dry air as well as warm, humid air to the city (Cornell University).

In the Caribbean, a wide range of clothing is not needed, as the climate stays the same year round. The weather is warm, with a wet season; droughts often occur near the end of summer (Gamble & Curtis, 2008, pp.265-267). “Temperatures along Caribbean island shores are remarkably steady year round. Over the year, the daytime high on a beach varies by only a few degrees,” Osborn (2009) says. Average year round highs range from 80°F to 90°F , while lows range from 70°F to 80°F. Precipitation varies from island to island, and even in different elevations on the same island (Osborn, 2009). There are much fewer storms in this locale, so water shortages are a major issue (Gamble, 2008, p.267; Osborn, 2009). Due to this climate, there is an emphasis on function and comfort among the lower classes, rather than fashion as a top priority.

Caribbean Culture

There are many customs and traditions in the Caribbean that make it a rich and interesting culture. Caribbean culture is a culmination of many different cultures, due to imperialism. Spanish, English, French, and Dutch cultures are very prevalent (Gilmore, 2000). “The many islands in the Caribbean Sea, with their white beaches, tropical vegetation, and marine life have attracted foreigners over many centuries, including gold-seeking Spanish conquistadors; British, French, and Dutch traders searching for lands and resources that would enrich their European aristocratic sponsors and themselves; and modern tourists, most of whom arrive on cruise ships,” states Chico (2010). There are also Asian, Indian, and African influences present (Gilmore, 2000). This diversity and vibrancy can be seen in how people dress (Buckridge, Overview of the Caribbean, 2010).

In the Caribbean, clothing can indicate class, status, group associations, or conceal identities (Buckridge, Overview of the Caribbean, 2010). Body decoration served these same purposes (Craik, 1994, p.154). Clothing was also important in recreational activities, like dance – a past time that all social classes enjoyed (Gilmore, 2000, pp.164-165). Skirts were made to aid movement or move in a certain way (Buckridge, Overview of the Caribbean, 2010).

One of the most notable cultural traditions in this area of the world is Caribbean Carnaval. Its roots lie in both African and European masquerades. Dress and costume during this celebration allow the islanders to be festive and freer in their individuality (Buckridge, Overview of the Caribbean, 2010). Buckridge also explains “Masquerade and masking, for some people, is a way to reconnect to their ancestral and African roots, or to establish a connection between the spiritual and supernatural world and the present.” (Overview of the Caribbean, 2010). The celebrations include lavish costumes and masks, bands, performers, parades and floats (Chico, 2010; Buckridge, Overview of the Caribbean, 2010). The battle between good and evil is a frequent theme in Carnaval costumes, as well as folktale characters and animals (Mack, 1994, p.100).

Buckridge describes the opulent costumes, rich materials and creation techniques very well in the Overview of the Caribbean:

Rara costumes are diverse and often consist of sleeveless silk tunics of bright colors embellished with sequins, pieces of glass and mirrors, pearls, and colorful scarves over matching sequined pants. Costumes of the mojo jonks who perform ritual maneuvers with batons are usually short pants and tunics made of cotton, silk, or synthetic fabric decorated with beads and sequins. Religious and cultural symbols in Haitian Vodou, such as a bird in flight, are often fashioned into the sequin designs. Some rara processions include characters dressed as royalty wearing tinsel-covered crowns or tiaras. The chausable-like rara tunics reflect French court and ecclesiastical influences, while the elaborate Vodou ritual flags were adapted from the French military standards as part of rara processions. Rara tunics and capes with rounded collars suggest the influence of Catholic capes and bishop’s copes, while the short fringed pants worn by the mojo jonk convey Amerindian dress influence and the spiritual alliance between the indigenous Taínos and African slaves . . . . Costumes in the Dominican Republic, as in Cuba and Puerto Rico, are often made from bright fabrics like satin and taffeta. Costumes are decorated with pieces of glass or mirror, bells, ribbons, whistles, miniature dolls, and strips of paper and fabric (2010).

In celebrations like these, masks can be just as important as the costumes. Masks symbolically transform a person into a different entity; in the scope of Carnaval, they often represent religious figures, folklore characters, historical figures, mythological creatures and spiritual beings (Mack, 1994).

American Fashion and Design Elements

The decade of the 1950’s was heavily researched in this project. This section focuses on American fashion, with an occasional worldly view of fashion.

Dresses. Shirtwaist and other dresses with simple fitted bodices were popular for daytime wear (Cunningham, 1994, p.338). “Daytime styles of 1957 followed an uncluttered, relaxed simplicity with hems of variable lengths, evening dress going all out for the exotic . . . . After sundown the skirt ranged from short, puffed harem hems to the newest fishtail trains, while the showing of an occasional knee-length by Dior,” (Wilcox, 2008, p.418). “Sack” or chemise dresses were also popular (Wilcox, 2008, p.417), and skirts were either “pencil-thin” or bouffant (Cunningham, 1994, pp.336-337). At the beginning of the decade, empire-waisted dresses regained popularity – “slim, high-waisted, full length gowns of elegant silks, chiffons and laces in long-line draperies with bead embroidery,” (Wilcox, 2008, p.417). Film stars (like the fictional Iris Tramm in Don’t Stop the Carnival) also influenced the 1950’s woman, “who wanted her every outfit to be suffused with elegance, sophistication and sex appeal,” (Peacock, 2005, p.173).

Blouses and Shirts. For men, dress shirts had narrow collars with pointed or rounded ends, and the button-down collar became a part of business wear (Cunningham, 1994, p.337). Pastel colors and small patterns were in fashion, as well as the versatile white nylon shirt (Wilcox, 2008, p.430; Cunningham, 1994, p.337). The bloused top with a larger collar was popular for women (Wilcox, 2008, p.417).

Shorts and Sportswear. Bermuda shorts were adapted from the breeches that Englishmen wore in the tropics and gained popularity in the 1950’s (Wilcox, 2008, p.430). These, as well as deck pants, jeans, sport slacks, pedal-pushers, capris, toreadors, golf shorts and ankle-length shorts and pants were worn by women and men (Cunningham, 1994, p.337-229). In the beginning of the decade pants were cut straight and less full, but began to taper and widen in the mid-1950s (Cunningham, 1994, p.337). Pleats, creases, and cuffs were seen on trousers – as well as plain colors, stripes, and plaids (Wilcox, 2008, p.426; Cunningham, 1994, p.337).

Suits. The neck-hugging collar was replaced with a cut-away neckline style for men (Wilcox, 2008, p.417-418), and a slimmer, straighter silhouette of men’s clothing developed (Cunningham, 1994, p.336). “The introduction of ready-to-wear, the development of mass-production techniques and the new man-made fabrics gave it new life, bringing to the man-in-the-street smart suits and sports jackets, and stylish trousers with permanent creases,” (Peacock, 2005, p.173). Female suits had straight or circular skirts and jackets that could match or contrast their skirt fabric (Cunningham, 1994, p.338).

Accessories. Most notably, women wore hats in all shapes and sizes – and more frequently than in past decades. Materials used to accompany the hats included ribbons, flowers, velvets, feathers, tulle, jewels, felts, buckles, and straws (Wilcox, 2008, p.421). Long, slim, pointy pumps were in style, as well as other slip-on types (Wilcox, 2008, p.432). Shorter gloves that accompanied short-sleeve coats, dresses, and suits were popular (Wilcox, 2008, p.422). Seamless nylon hose and wide belts were also common (Cunningham, 1994, pp.338-339). Male hats had lower crowns and narrower brims (Cunningham, 1994, p.338). Jeweled hair combs and hairpins graced up-do hairstyles for women, and men wore their hair in crew cuts or English hairstyles (Wilcox, 2008, pp. 422-432). Many women preferred shorter haircuts that were styled closer to the head; longer hair was curled and shoulder-length (Cunningham, 1994, p.337). “Wide picture necklines have influenced the flair for costume jewelry, a particular note being the chandelier earrings. Fabulous brooches, clips, tiaras and long necklaces are modish,” says Wilcox (2008, p.425).

Caribbean Fashion and Design Elements

Style and Function. In addition to American design elements, the Caribbean had its own aspects of dress. Light fabrics were used due to the tropical climate and vibrant colors were common (Buckridge, 2010). Caribbean fashion is a culmination of dress from many other ethnicities, explains Buckridge:

Some ethnic dress brought to the region has been adapted, nurtured, and maintained over the centuries, such as the Indian sari that is worn by women of Indian descent in Trinidad and Guyana, or the brightly colored batik prints of Indonesian origin in Paramaribo, Suriname, and the African woman’s headwrap, which is popular among many black women . . . . Jamaican dress at first was influenced by two dominant aesthetics, African and European, but other groups, those of non-African and non-European ancestry, also brought their customs in dress to Jamaica in the late nineteenth century and onward (2010).

Purpose and function are also important. Clothing may be chosen on flattering or protecting the body, communicating status, or representing a social group (Buckridge, 2010). Dresses worn by women at dance halls eroticized the body and moved well, while Bermuda shorts for men were favored in this tropical climate (Buckridge, 2010, Overview).

Fabric. Madras cloth was the primary fabric used in Caribbean clothing – especially for long skirts, headwraps, blouses, aprons, and pants (Buckridge, 2010, Overview). Headwraps were also made from silk and satin (Chico, 2010). Many fabrics from around the world were imported to the Caribbean (Chico, 2010). Cotton and linen were other lightweight fabrics seen in many clothes (Buckridge, 2010). While colors of all shades were popular, some had deeper meanings as well – red was associated with blood and slavery, yellow for gold and wealth, green for the lush environment, and black for the beauty of African people (Chico, 2010).

Headwraps and Hats. Headwraps have a wide variety of meaning, function, and purpose. They can indicate ethnicity, legal status, religious affiliation, and social position (Chico, 2010, Buckridge, 2010). Depending on the island, people of all socioeconomic statuses wore turbans and other headwraps, but the materials varied (Chico, 2010). For men, the panama straw hats and boaters were in fashion (Chico, 2010). Dazzling, tall headpieces were used in Carnaval celebrations and included large feathers, exotic flowers and sequins (Chico, 2010). Berets were associated with Rastafarians and knitted with red, yellow, green, and black designs (Chico, 2010). Pieces of fabric were used by outside workers in a makeshift headwrap that would cover and protect the ears, neck, and shoulders (Chico, 2010).

Swimwear. With the discovery of nylon, swimwear in the 1950’s became much more slimmed-down and form fitting (Craik, 1994, p.141). Bikinis were popular in this time period and replaced many one-piece female bathing suits (Craik, 1994, p.149). Latex, jersey, and cotton were all used in men’s swimwear, which became skimpier as the decade progressed (Wilcox, 2008, pp.424-425). Many swimsuits came with wrap-around skirts for modesty when beachgoers went from the beach to club restaurants (Wilcox, 2008, p. 424). One-piece and strapless swimsuits for women had foundational support built into them (Craik, 1994; Wilcox, 2008).

Show Analysis

Original CD Track Listing

Intro: The Legend of Norman Paperman/Kinja — 7:01

Public Relations — 3:57

Calaloo — 3:15

Island Fever — 4:34

Sheila Says — 3:55

Just an Old Truth Teller — 3:34

Henry’s Song: The Key to My Man — 3:10

Kinja Rules — 3:48

A Thousand Steps to Nowhere — 5:24

It’s All About the Water — 2:21

Champagne Si, Agua No — 1:44

Public Relations (Reprise) — 1:25

The Handiest Frenchmen in the Caribbean — :50

Hippolyte’s Habitat (Qui Moun’ Qui) — 3:10

Who are we Trying to Fool? — 4:35

Fat Person Man — 3:28

Up on the Hill — 4:10

Domicile — :37

Funeral Dance — :51

Time To Go Home — 6:03

Adapted Scene Breakdown

Due to the lack of a libretto, scenes between the musical numbers were added in based on research, commentary, and the original novel. Small changes were made in the order, addition, and subtraction of musical numbers. For example, “Green Flash at Sunset” was a short song in the original production that never made it onto the soundtrack, much to the dismay of Wouk (Buffett, Don’t Stop the Carnival!, 1998). “Steel Drum Panic” is based on an instrumental from another Buffett CD. These changes were made to improve clarity and order of the story, substitute unobtainable information about the original script, and are also suggestions of ways to improve the production. This adapted list of scenes is for the purpose of this project only.

ACT ONE

Intro: The Legend of Norman Paperman – (Carnival A) – Carnival is in full go; song signifies that the story will begin in the past.

Scene – Lester & Norman arrive in Kinja.

Island Fever – Norman is enchanted by the island, and describes the magic of what he is seeing and feeling. (Originally Song #4).

Scene – Lester & Norman discuss plans with others to buy the Gull Reef Club.

Scene – Norman meets Iris.

Public Relations – Norman speaks of his past; and realizes what he wants his future to be. Iris tries to warn him that things are not as they seem in the Caribbean.

Scene – Atlas leaves and tells Norman not to worry about finances.

Scene – Iris shows Norman around the Island.

Calaloo– Norman learns more about the island culture and the employees of the Gull Reef Club; introduction to Sheila; foreshadowing future problems that could arise

Scene – Norman leaves for NYC. Sheila talks to Iris.

Sheila Says – After Norman leaves, Iris realizes she has feelings for him. She reflects on her past, present and future.

Scene – Sardi’s – Norman and Henny agree to move forward with buying the club.

Scene – Norman realizes what Lester has done (swindled him out of using any money from Lester). Norman must sell all his contacts/information.

Just an Old Truth Teller – Lester explains the kind of man he is / as they fly to Kinja to close the deal.

Scene – Lester and Norman close the deal. Lester leaves Kinja.

Henny’s Song: The Key to My Man – Henny is reluctant to move forward with Norman’s plans, but wants to make her husband happy.

Scene: Water running low; Norman misses the barge.

Kinja Rules – Senator Pullman arrives to discuss the water shortage and other issues going on with Norman & the club, while explaining how things work differently in Kinja.

Scene – Loud noises interrupt Norman and he sees that Tex Akers & his crew have torn a huge hole in the club.

Scene – Thunderstorm / Party – but no rain for the Gull Reef Club.

Scene – The Gull Reef club runs out of water.

A Thousand Steps to Nowhere – Norman and Iris climb the thousand steps to find Gilbert, who knows how to prime the cistern pump; while Henny sings that she is finally ready to come down to Kinja and leave NYC.

Scene – Gilbert primes the pump with Norman.

It’s All About the Water – Celebration of water returning (via the emergency tank)

Scene – Maids quitting; Lorna left; Norman buys water and the trucks arrive; guests begin to leave the resort because of multiple problems; Tex Akers stops remodeling the club and leaves a hole in the wall.

Scene – Earthquake / Cistern breaks / Tom Tilson asks Norman to host his party

Champagne Si, Agua No – Norman hosts a free champagne party in the lobby for his guests because of all the trouble and the water shortage. Meanwhile, a huge thunderstorm is occurring.

Scene – Debate Over Hippolyte w/ Sheila

Public Relations – Reprise – The Governor suggests that Norman should give up his investment and go home – that nothing good can come of it. Norman declines, and “gets his second wind” – he is now more determined than ever to fix the club. He ends with ordering someone to find Hippolyte.

ACT TWO

The Handiest Frenchman in the Caribbean – Some time has passed and Hippolyte has fixed the cistern, patched the hole in the wall, and repaired a number of other things at the club. Everyone is rejoicing, especially Norman, with having things go right for a change.

Scene – Paperman talks to Hippolyte; he is impassive and heads off. Norman learns more about Hippolyte from others (his mental institution days, attempted rapes, and how he cut off the head of a cop in the past).

Hippolyte’s Habitat – The dispassionate and unresponsive Hippolyte sings this solo alone, with no one else on stage. Perhaps it is a look into his mind rather than him actually speaking to another person/audience. He lays out exactly what he thinks and what he intends to do – take over the club.

Scene – Party w/ Amy & Tom Tilson on a boat; she agrees to lower what Norman owes her.

Scene – Iris & Norman have a date.

Green Flash at Sunset – Norman is content yet reflective about love and his past. He sings this to Iris as they both reminisce about days gone by.

Who Are We Trying to Fool? – Iris and Norman head back to her house and give into temptation. Sheila explains how dangerous the situation has now become.

Scene – Next day…. preparations for Tilson party are underway; Norman’s family arrives; and just as things are all falling into place nicely, Paperman finds out Atlas fired Hippolyte.

Fat Person Man– Sheila warns Norman about the consequences of Lester and Hippolyte being in the same place at the same time – Hippolyte is enraged and will behead Lester if he comes across him. Norman frets and tries to plan how he can keep them apart, and manage the two parties that will be going on that night (the Tilson party and the beach barbeque).

Scene – The Tilson Party begins / Norman searches for Hippolyte / Iris causes a huge scene at the party.

Up on the Hill– The upper class of Kinja and other notables, attending the Tilson party, sing about themselves. It’s a slight parody as they muse about “owning the breezes”, managing their blenders, avoiding high taxes, and what their lives are like. It’s a stark contrast to the lives that the native Kinjans lead.

Steel Drum Panic [New Song] – The group tries to catch Hippolyte; Sanders and Norman bring a passed-out Iris back to her house; Hippolyte appears and slashes at Meadows; Meadows is sent to the vet; Esme is sent to the Hospital.

Funeral Dance (Carnival B); Extended Dance Scene; Don’t Stop the Carnival reprise Day after– Carnival is now in full swing, and amidst the joy and partying – there is still trouble for Norman. Someone is shot in the Gull Reef club bar, and Iris rushes to her dog, getting in a fatal car accident along the way.

Scene – Norman learns the news of Iris; Henny & Norman talk about the affair he had with Iris, and they discuss selling the club to Lionel so that they can return to their lives in NYC.

Time to Go Home (Intertwined with Carnival C Scene)

Below is the track “Green Flash at Sunset”, a song so special to Wouk, Jimmy added it onto a media portion of his CD

after the other songs were recorded (Don’t Stop the Carnival CD). This song has been included in this project.

EXPLANATION OF ADAPTATION: Author’s Note

When adapting the track listing and adding scenes, I drew upon my memories of when I first sat down and listened to the CD in full [while thinking of this project]. I’ve heard this music since I was young, but really understood it better as an adult.

I have been trying to obtain the script since 2012 with no success.

My father has been an invaluable resource to bounce ideas off of and discuss this project with. He is the only person close to me that has heard of Don’t Stop the Carnival and remembers a lot about it. He is more familiar with the CD, but has read the novel in the past.

I mention my father because when I first analyzed the CD, I had an enormous list of questions for him. Who was the actress Norman fell in love with? Iris Tramm’s name is never mentioned on the album. No one calls her name out or references her. Yet she is one of the two major characters. Why do some of the tracks seem out of order? Norman celebrates about how he turned the water back on, and then immediately after there’s a song about him losing water! What happens at the end? There is no song on the album that alludes to the climax of the story and falling action. It simply goes from Sheila and Norman planning to keep Hippolyte away from Lester; a song from the Hill Crowd speaking about who the rich people on the island are; a little narration about Carnival Day, and the finale of “Time to Go Home” (Norman deciding to leave). WHAT made him decide to leave? What happened in that chunk of time that was missing?

This was a huge plot gap that is confusing to a first-time or casual listener! You must have seen the show or read the novel to understand it. And recordings of musicals should STAND ALONE as much as possible. Not every person has access to seeing a show live or even getting a script or source material. This is one of the major flaws of the album, and I set out to fix that.

The changes I made are not simply personal preference or opinion – I am drawing upon the wealth of information I gathered in my directing, acting, technical design, playscript analysis, history of theatre, dramatic literature, and other theatrical classes.

I opened the show as it was normally done – with the Legend of Norman Paperman. But after this first musical number, I diverged from the original a bit. The CD has Public Relations after this, then Calaloo, and then Island Fever. I changed the order based on ease of the audience understanding the plot. Sometimes events that happen on the CD just don’t seem to be in order or make the most sense that they could.

Due to Public Relations being the song where Norman definitively chooses to throw his old life away and buy the Gull Reef Club – I felt as if this didn’t make sense to have it as the second song in the musical (and the first time we see Norman). I felt we needed to see him more entranced by the island first – to see the reason behind his decision. Island Fever is a song that does exactly this. He describes the magic of Kinja and what he sees and feels.

After a few short scenes, we then bring in Public Relations. In this song, Norman meets Iris, and makes his big decision to move to Kinja.

After this, the next major musical number is Calaloo. So, essentially, the only change has been the placement of the song Island Fever in this part of the production. Calaloo is an excellent song that foreshadows all of the problems that are to occur, and also introduces us to some of the real island culture.

As Iris’ solo number occurs after Norman leaves, there is a transitional scene before it showing this. Lester and Norman leave, and Sheila and Iris have a small conversation. This is what prompts Iris to sing her ballad.

Listening to the CD, we do not get much of a glimpse of New York City. There is some of the NY attitude in Just an Old Truth Teller, but this song could really occur in either setting. So, in between Sheila Says and Just an Old Truth Teller there are short scenes taking place in NYC. This shows the audience what Norman is leaving behind – and shows visually and metaphorically the contrast of both lifestyles. In addition, it suggests passage of time.

After arriving back to Kinja and officially closing the deal, we are transported back to NY once again for Henny’s solo number. She is reluctant to move forward with the plan but knows she has to.

There is a short scene added with Norman realizing his water supply is low at the club, and missing the water barge. In the midst of trying to solve this problem, Senator Pullman shows up and they sing about Kinja Rules. A few more scenes added after this event include Tex Akers tearing a giant hole in the side of the club, a huge thunderstorm and party, and the pivotal moment where the Gull Reef completely runs out of water.

This brings us into A Thousand Steps to Nowhere, which occurs in both NY (where Henny sings) and Kinja (where Norman and Iris sing). It’s All About the Water comes next, but does not jump straight into Champagne Si, Agua No. Instead, there are short scenes explaining the catastrophes going on. This includes the major catastrophe in Act I – the cistern overflowing and breaking. Then comes the Champagne party, prompted by this major event.

A small scene introduces us (via Sheila) to the person that can save Norman – Hippolyte. Norman decides he will not quit and keep forging ahead to save his club.

Act Two opens with The Handiest Frenchman in the Caribbean – which is a good number, but only 50 seconds long. It would work well if expanded.

Before Hippolyte sings his solo, I’ve added a short scene where Norman learns about Hippolyte’s past. This is due to Hippolyte’s solo being – less of a threat – without more exposition. Without a scene learning about Hippolyte’s days in the mental institution, cutting off the head of a police officer, and other dangerous things – Hippolyte’s Habitat seems more of a soft threat. Hippolyte merely says he has some plan to make the owners disappear so he can get the club – and also sings about how he can “instill some fear”. While one of my favorite songs in the show, it needed more exposition. We need to feel that, “Oh NO!” feeling when Lester rudely fires Hippolyte later in Act 2 – we need to understand that Hippolyte is an incredibly dangerous threat.

Continuing on with a few small scenes, including a date between Norman and Iris – Green Flash at Sunset has been included. I referenced the original novel and tried to match up when the green flash occurs based on other events, and fit it into act two appropriately.

After Who Are We Trying to Fool?, another exposition scene occurs. This prepares for the climax to begin. Just as everything seems to be falling into place for Norman, things get complicated. Henny and his family arrives, for one, building friction between Norman and Iris. The preparations for the Tilson party are underway, and Norman must make sure it is perfect to ensure his longevity on the island. And lastly, we learn that Lester has arrived, made a scene with Hippolyte, and fired him. This leads us into Fat Person Man where Sheila and Norman discuss the danger and stakes of the situation.

As the search for Hippolyte begins, so does the Tilson party. And we see Iris causing a huge scene that reveals what has happened between her and Norman. She is taken away from the party. This was alluded to in the album notes by Wouk.

Up on the Hill introduces us to the hill crowd more and Tilson party. It is a moment for us to breathe and smile, as the number is relaxed, light, and teasing. A full contrast to what happens next: the number I dubbed Steel Drum Panic. This is actually an instrumental from Margaritaville Cafe – Late Night Menu called Pan Classique in B Minor (Mad Music).

The subtitle alone explains that it is a heart-racing, panic-inducing sort of track – yet still tropical, as the main instrument used is the steel drum!

After this song addition would be Funeral Dance. The day after – where Carnaval is in full swing. There is an extended dance scene added to this drum-heavy instrumental (Carnival “B”) and perhaps it could even be intertwined with a sort of Don’t Stop the Carnival/Intro reprise.

After a scene with the falling action of a shooting at the Gull Reef bar, Iris getting in a fatal car accident, and Norman learning of her death – Henny and Norman discuss everything that has happened. They decide to go home, which is sung about in the final musical number.

Physical & Psychological Character Analyses

Characters were analyzed by description in the original novel, commentary on the musical CD, and their words and actions in both source materials. What the characters say about themselves, and what other characters say about them, gave great insight to their character quirks and personality traits (Gillette, 2007, p.442).

Norman Paperman is a middle-aged, medium-built New Yorker who is a fashionable dresser. He is incredibly ambitious and courageous. Often, Norman is stubborn, high-strung, and anxious when he deals with the catastrophic problems he faces with his hotel. He is a gambler, who has confidence and plenty of humor. Norman recently recovered from a heart attack, and is not supposed to exert himself or he gets very short of breath. Unfortunately, this happens a lot as he runs around the island trying to fix multiple problems at the same time.

Iris Tramm, whose stage name was Janet West, is a “beautiful and bitter” actress (Dolen, 1997). She is disillusioned and sad due to some tragic events in her past, yet remains romantic and flirty. Iris also has a good sense of humor and likes to tease people. She is regal and composed when sober, but broken and dangerous when she drinks too much. Iris is described as being a tall blonde with a lovely face and “strikingly brilliant” eyes (Wouk, 1965).

Lester Atlas is Norman’s friend and the person who pushes him to purchase the Gull Reef Club. He is well known as a corporate raider, and many people recognize him from the cover of Time. Not only is Lester greedy, manipulative, and shady; but also loud, rude, self-important and offensive. He has a boisterous, shameless, and indulgent attitude. Lester is a middle-aged extrovert with a thick skin and has no remorse for what he does. In fact, he thinks of himself as a sort of hero – described in the number “I’m Just an Old Truth Teller” (Buffett, Don’t Stop the Carnival!, 1998). Wouk (1965) describes him as “a big oyster-pale fellow . . . . with a thick bald head like a bread loaf rising out of fat shoulders.” All of these traits make Lester a very alarming, off-putting, and comical character.

Norman’s wife Henny is a beacon of support for his wild endeavors. She is firm in her opinions, but also easy-going, lighthearted and teasing. Henny is a very observant woman who is kind and friendly. She is concerned with making sure her husband is happy, and is worrisome at times when she thinks of changing her lifestyle completely. Henny’s physical characteristics are that of a petite, round-faced brunette, similar in age to Norman.

The glue that holds Norman and his club together is Sheila, the club’s chef. She’s worked there for many years and is a resourceful, smart, strong woman. Sheila helps Norman in every disaster that comes his way, and gives good advice to those around her. She’s also wise, keen, and calm under pressure. Wouk (1965) describes Sheila: “a mountainous irascible black woman with dark eyes and thick satanic eyebrows.” She is a minor character in the novel, but a main character in the musical – often advancing the plot or explaining what is going on.

Another major force in Don’t Stop the Carnival is Hippolyte Lamartine, a former handyman of the Gull Reef Club. His reputation is that of an unstable, sometimes deranged, unsocial brute. He is excellent at his job, and knows all the ins-and-outs of the club. However, Hippolyte is extremely dangerous, short-tempered, and carries a machete with him at all times. After many catastrophes, Norman decides to hire Hippolyte back as the handyman, and he fixes all of his problems. When Lester Atlas comes back to the island a few weeks later and fires the handyman, Hippolyte goes after him on a murderous rampage during the climax of the story. With a tall, strong build, mixed complexion, and a hat that always shades his face, Hippolyte is a physically menacing character as well.

Design Concept

TO BE CONTINUED

IN PROGRESS OF UPDATING!

Sources and Further Reading

(1997). Coconut Telegraph, 13 (1).

(1998). Coconut Telegraph.

(2001). Coconut Telegraph, 17 (2).

(2001). Coconut Telegraph, 17 (2).

Beckwith, D., & Beckwith, N. (2009, August 30). Don’t Stop the Carnival, Plead Wouk and Buffett. Retrieved January 2, 2014, from Florida Keys News: http://keysnews.com/node/16458

Buckridge, S. O. (2010). Jamaica in the Nineteenth Century to the Present. In M. B. Schevill (Ed.), Encyclopedia of World Fashion: Latin America and the Caribbean (Vol. II, pp. 264-269). New York: Oxford University Press.

Buckridge, S. O. (2010). Overview of the Caribbean. In M. B. Schevill (Ed.), Encyclopedia of World Fashion: Latin America and the Caribbean (Vol. II, pp. 247-250). New York: Oxford University Press.

Buffett, J. (1997). Coconut Telegraph, 13 (1).

Buffett, J. (1997). Coconut Telegraph, 13 (1).

Buffett, J. (1998). Coconut Telegraph.

Buffett, J. (Composer). (1998). Don’t Stop the Carnival! [J. Buffett, Performer] [CD]. New York: M. Utley.

Buffett, J. (1997). Interview. Coconut Telegraph, 13 (3).

Burton, R. D., & Reno, F. (1995). French and West Indian: Martinique, Guadeloupe, and French Guiana Today. (A. J. Arnold, Ed.) Charlottesville, VA: University Press of Virginia.

Chico, B. (2010). Caribbean Headwear. In M. B. Schevill (Ed.), Encyclopedia of World Fashion: Latin America and the Caribbean (Vol. II, pp. 290-300). New York: Oxford University Press.

Cornell University. (n.d.). The Climate of New York. Retrieved February 21, 2014, from http://nysc.eas.cornell.edu/climate_of_ny.html

Craik, J. (1994). The Face of Fashion: Cultural Studies in Fashion. London: Routledge.

Cunningham, R. (1994). The Magic Garment: Principles of Costume Design. Prospect Heights, IL: Waveland Press, Inc.

Dolen, C. (1997). Don’t Stop This Carnival! Coconut Telegraph, 13 (4).

Eicher, J. B. (2010). Encyclopedia of World Dress and Fashion. In M. B. Schevill (Ed.), Latin America and the Caribbean (Vol. II). New York: Oxford University Press, Inc.

Furguson, J. (1999). A Traveller’s History of the Caribbean. New York: Interlink Publishing Group, Inc.

Gamble, D. W., & Curtis, S. (2008). Caribbean Precipitation: Review, Model, and Prospect. Progress in Physical Geography , 32 (3), 265-276.

Gillette, J. M. (2005). Theatrical Design and Production (6th ed.). New York: The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc.

Gilmore, J. (2000). Faces of the Caribbean. London: Latin America Bureau Ltd.

Heyse-Moore, D. (2010). Trinidad in the Nineteenth Century. In M. B. Schevill (Ed.), Encyclopedia of World Fashion: Latin America and the Caribbean (Vol. II, pp. 277-284). New York : Oxford University Press.

Humphrey, M., & Lewine, H. (1996). The Jimmy Buffett Scrapbook (2nd ed.). New York: Kensington Publishing Corporation.

Jimmy Buffett Presents Herman Wouk’s Don’t Stop the Carnival. (2001). Coconut Telegraph , 17 (2).

Langley, L. D. (1989). The United States and the Caribbean in the Twentieth Century (4th ed.). Athens: The University of Georgia Press.

López, R. J. (2010). Dress and Dance in Puerto Rico. In M. B. Schevill (Ed.), Encyclopedia of World Fashion: Latin America and the Caribbean (Vol. II, pp. 270-276). New York: Oxford University Press.

Mack, J. (1994). Masks and the Art of Expression. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc.

Maingot, A. P. (1994). The United States and the Caribbean. San Francisco: Westview Press.

Martin, T. (2012). Caribbean History: From Pre-colonial Origins to the Present. Boston: Pearson Education, Inc.

Oostindie, G. (2005). Paradise Overseas: The Dutch Caribbean. Oxford: Macmillan Publishers

Osborn, L. (2009). Caribbean Weather: Annual Temperature & Rainfall. Retrieved February 21, 2014, from Current Results: http://www.currentresults.com/Weather/Caribbean/average-annual-temperature-rainfall.php

Padilla, A. (2003). The Tourism Industry in the Caribbean After Castro. Retrieved March 27, 2014, from http://www.ascecuba.org/publications/proceedings/volume13/pdfs/padilla.pdf

Pattullo, P. (1996). Last Resorts: The Cost of Tourism in the Caribbean. London: Cassell & Co.

Peacock, J. (2006). Costume: 1066 to the Present (3rd ed.). London: Thames & Hudson, Ltd.

Peacock, J. (2005). The Complete Fashion Sourcebook: 2000 Illustrations Charting 20th Century Fashion. New York: Thames & Hudson, Ltd.

San Miguel, P. L. (2005). The Imagined Island: History, Identity, and Utopia in Hispaniola. Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press.

Schevill, M. B. (2010). Overview of Dress and Fashion in Latin America and the Caribbean. In M. B. Schevill (Ed.), Encyclopedia of World Fashion: Latin America and the Caribbean (pp. 3-22). New York: Oxford University Press.

Smith, R. F. (1994). The Caribbean World and the United States: Mixing Rum and Coca-Cola. New York: Twayne Publishers.

Sommers, A. (1997). Don’t Stop the Carnival. Coconut Telegraph , 13 (5).

Tselos, S. E. (2010). Creolized Costumes for Rara, Haiti. In M. B. Schevill (Ed.), Encyclopedia of World Fashion: Latin America and the Caribbean (Vol. II, pp. 257-263). New York: Oxford University Press.

Tselos, S. E. (2010). Vodou Ritual Garments in Haiti. In M. B. Schevill (Ed.), Encyclopedia of World Fashion: Latin America and the Caribbean (Vol. II, pp. 251-256). New York: Oxford University Press.

Wilcox, R. T. (2008). The Mode in Costume: A Historical Survey with 202 Plates. Mineola, NY: Dover Publications, Inc.

Wouk, H. (1965). Don’t Stop the Carnival. New York: Little, Brown & Co.

Reference & Contact Information

These designs are © Kaedra Lynn Herink and may not be reused, re-posted, edited, sold, or transferred in any manner or format.

Don’t steal – please contact me first. I’ll be happy to help you.

To reference any original [text] material on my website, here are some facts that may help with your citation:

Author: Kaedra Lynn Herink

Website created: March 30, 2014

Website last updated: March 8, 2021

Web Page URL: https://www.enchantedseastudio.com/thesis-dont-stop-the-carnival

Name of Web Page: Thesis - Don’t Stop the Carnival!

Website URL: http://enchantedseastudio.com

Name of Website: Enchanted Sea Studio

Credentials/Degrees:

A.A.B. in Computer Information Systems & B.A. in Theatre Arts

Please feel free to e-mail me with questions, thoughts or concerns.